World Class Eye Care Heading link

Expert ophthalmologists at Illinois Eye & Ear at UI Health practice in a world class setting at UI Health’s new Specialty Care Building. From outpatient eye surgery to routine and complex visits, our experts provide eye care all in the same state-of-the-art building.

Education Heading link

Learn more about our Residency program

The medical education ophthalmology residents receive at the Illinois Eye & Ear Infirmary will assist them throughout their career. We make sure our residents are among the best-prepared candidates for fellowship or job interviews.

Learn about the 12 fellowship programs offered in the Department of Ophthalmology.

Each fellowship covers a different subspecialty.

Fellowship details

Global Ophthalmology Heading link

Leaders in Vision Research Heading link

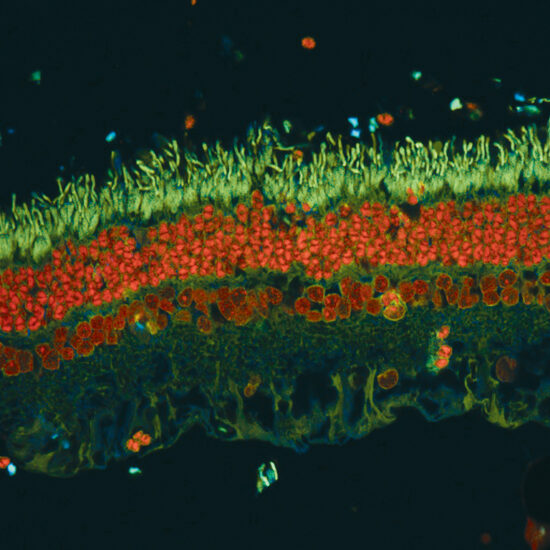

The Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences maintains a tradition of excellence in collaborative and interdisciplinary vision science research and is dedicated to understanding, treating, and preventing blinding eye disease.