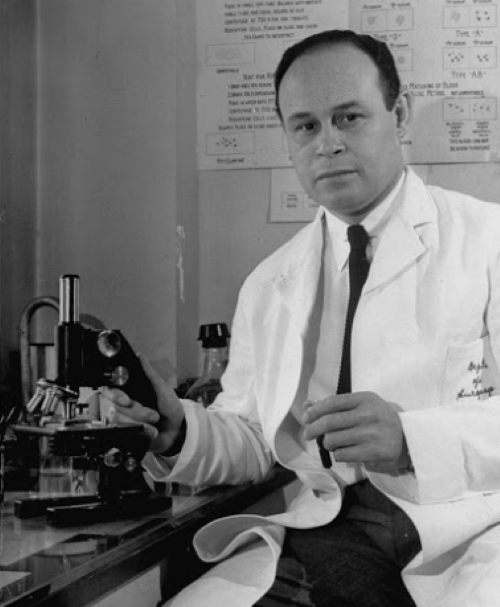

Charles Richard Drew, MD, MSD

Physician

Physician, surgeon, educator, equality advocate, and researcher

Charles Richard Drew, MD, MSD Heading link

The Department of Medicine Inclusion Council honors and celebrates the life and accomplishments of Charles Richard Drew, MD, MSD, (June 3, 1904 – April 1, 1950). Dr. Drew may be best known as the “Father of the Blood Bank”. He invented bloodmobiles, mobile donation stations that could collect and refrigerate blood. He is the first African-American to receive a doctor of medical science degree in 1940 from Columbia University. Drew’s accomplishments were recognized when he became the first African-American surgeon selected to serve as an examiner on the American Board of Surgery and with his 1941 appointment as director of the first American Red Cross Blood Bank.

Charles Drew was born in Washington, D.C. and won an athletics scholarship to Amherst College in Massachusetts, where he played football and was on the track and field team, and graduated in 1926. The impact of the death of his sister Elsie at 13 from the flu pandemic and a biology professor, shifted his interest from electrical engineering to medicine. After college, Drew spent two years as a professor of chemistry and biology, the first athletic director, and football coach at the historically black private Morgan College in Baltimore, Maryland, to earn money to pay for medical school.

Drew decided to attend McGill University College of Medicine in Montreal, Canada. While there he achieved membership in the medical honor society Alpha Omega Alpha, won a scholarship prize in neuroanatomy, and staffed the McGill Medical Journal. He ranked second in his graduating class where he received his Doctor of Medicine and Master of Surgery degrees in 1933. Drew’s interest in transfusion medicine began during his internship and surgical residency at Montreal Hospital (1933-1935) working with bacteriology professor John Beattie on ways to treat shock with fluid replacement. Drew’s first appointment as a faculty instructor was for pathology at Howard University from 1935 to 1936, then joined Freedman’s Hospital, as an instructor in surgery and an assistant surgeon.

Daniel Hale Williams, MD Heading link

In 1938, Drew began graduate work at Columbia University in New York City on the award of a two-year Rockefeller fellowship in surgery. He spent time doing research at Columbia’s Presbyterian Hospital and wrote a doctoral thesis, “Banked Blood: A Study on Blood Preservation”. It was through this blood preservation research where Drew realized blood plasma was able to be preserved, two months, through the separation of liquid blood from the cells. When ready for use the plasma would then be able to return to its original state via reconstitution.

Drew was headhunted by British officials during World War II to create a blood bank for their soldiers and civilians and went to New York City as the medical director of the United States’ Blood for Britain project, a project to aid British soldiers and civilians by giving U.S. blood to the United Kingdom. It was here that Drew helped set the standard for other hospitals donating blood plasma to Britain by ensuring clean transfusions along with proper aseptic technique to ensure viable plasma dispersals were sent.

Daniel Hale Williams, MD Heading link

Drew created a central location for the blood collection process where donors could go to give blood, beginning a huge operation of recruiting volunteers in America to give a pint of blood where plasma was separated, stored, tested, and shipped to Britain by the Red Cross. The project operated successfully for five months, with total collections of almost 15,000 people donating blood, and over 5,500 vials of blood plasma.

Ironically, the national blood collection project was sullied by racism from the start. Blood donations and plasma for Blood for Britain had been segregated, on the assumption that the British would prefer this. The Red Cross pilot project, at the insistence of the armed forces, excluded black donors. This policy was maintained when the National Blood Donor Service officially began in November 1941, provoking protest from the black press and the NAACP, among others. In January 1942, the Red Cross announced that it would accept blood from black donors, but would segregate it, a policy that remained until 1950.

Daniel Hale Williams, MD Heading link

Drew, objected to this policy–there was no scientific evidence, of any difference between blood of different races, and the policy was insulting to African Americans, who were just as eager to contribute to the war effort as anyone else. He wrote and spoke about this frequently during the war years; as he noted in his NAACP Spingarn Medal (for his blood plasma work) acceptance speech in 1944, “It is fundamentally wrong for any great nation to willfully discriminate against such a large group of its people. . . . One can say quite truthfully that on the battlefields nobody is very interested in where the plasma comes from when they are hurt. . . . It is unfortunate that such a worthwhile and scientific bit of work should have been hampered by such stupidity.”

Ending his tenure with the Red Cross, Drew returned to Howard University in 1941 as Head of the Department of Surgery and Chief of Surgery. He was dedicated to training Black surgeons and campaigning to get them better access and recognition in the medical world and campaigned against the exclusion of Black physicians from medical societies.